Articles & Videos

What is orthographic mapping and why is it important?

Categories

Subscribe to our newsletters

Receive teaching resources and tips, exclusive special offers, useful product information and more!

Back to Research & Case Studies articles & videos

What is orthographic mapping and why is it important?

Sound Waves Literacy 1/6/23

Have you ever wondered how skilled readers can automatically and effortlessly recognise words? The process that allows us to recognise between 30,000 – 80,000 words in an unconscious manner is called orthographic mapping 1.

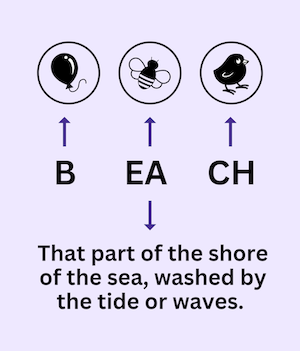

Orthographic mapping is a cognitive process in which the sound, spelling and meaning of words are mapped together and permanently stored in our memory 3 5. When readers encounter unfamiliar or new words, decoding (applying knowledge of phoneme–grapheme relationships) is used as a strategy for reading. Once we have read a word on multiple occasions, it is recognised immediately, and its pronunciation and meaning are activated 5.

Orthographic mapping allows readers to:

- recognise words effortlessly, automatically and accurately

- process graphemes at a rapid rate

- read words fluently in various fonts or cases

- process the letters in the word simultaneously while reading.

Orthographic mapping is not:

- memorising words by how they look

- recognising words as pictures, e.g. being able to recognise brands like Pepsi or McDonald’s based on colours, shapes, fonts and curvature

- reading words as a whole – neuroimaging and eye-tracking research has proven that skilled readers still process every grapheme of a word

- applied to high-frequency words only.

How does orthographic mapping occur?

Reading researchers suggest there are four major phases of word reading and spelling development that children progress through 1 3 5. The first is the Prealphabetic phase, which precedes reading. At this level children know that print conveys meaning, they might know the names of letters in the alphabet and they may be able to recognise brand names or their own name (but only from rote learning and memorisation) 2 3 4.

The next two phases are Partial Alphabetic and Full Alphabetic. The major characteristic of these phases is that children learn that graphemes represent phonemes 1 4. Children use this knowledge to decode (sound out) unknown words. They practise segmenting and blending, and build a small bank of words that they are able to automatically and accurately recognise 1. Children at Partial and Full Alphabetic stages are also learning grapheme patterns and applying this knowledge to spelling 3.

Lastly, the Consolidated Alphabetic phase includes rapid recognition of words and the ability to process new words with proficiency and ease 2. In this phase students can confidently decode unknown words they encounter, and have an established and growing bank of words they can automatically and accurately recognise (i.e words they have orthographically mapped) 3. They also have knowledge of prefixes, suffixes, and Greek and Latin roots, and apply this knowledge when reading or spelling new words 1.

How can we help children orthographically map words to become skilled readers and spellers?

| Components that effectively support reading and spelling | Components that don’t effectively support reading and spelling |

|---|---|

| Building strong phonemic awareness skills, including blending, segmenting and manipulating phonemes 2 3. | Whole-word activities, as they do not foster the connection between each phoneme and grapheme correspondence, nor allow transfer of this knowledge to new words. |

| Following a scope and sequence that explicitly teaches phoneme–grapheme relationships, particularly one that follows a logical order and progresses from simple to more complex 2 3. | Memorising words as a whole or encouraging rote learning, e.g. Look, cover, write, check. As our brains cannot memorise many words, this is not an effective strategy for long-term retrieval. |

| Practising segmenting words into their individual phonemes and associated graphemes 1. |

Tasks such as word shapes, which emphasise the look and form of the word and not the relationships between the sounds and letters. |

| Supporting vocabulary development through tier one, two and three vocabulary. A carefully curated set of words can be used to demonstrate the different ways to represent each sound, investigate the common position of a sound in a word, teach letter patterns (grapheme choices), explore morphology and teach the meaning of unfamiliar words. | Giving students traditional spelling lists that group unrelated words together, don’t link to morphology or explore the meaning of the words. |

| Using decodable readers so students can read phoneme–grapheme relationships in context and practise blending taught phoneme–grapheme relationships together. | Using predictable texts, as these encourage students to look at the pictures and take a guess rather than processing the letters in words. |

References

Moats, L 2020, Speech to print: Language essentials for teachers, Brookes Publishing, Baltimore, Maryland. ↩

Dehaene, S 2019, Reading in the brain: The new science of how we read, Penguin Books, New York.↩

Ehri, LC 2013, ‘Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning’, Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(1), 5–21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2013.819356. ↩

Seidenberg, M 2018, Language at the speed of sight: How we read, why so many can’t, and what can be done about it, Basic Books, New York. ↩

Kilpatrick, D 2015, Essentials of assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey. ↩